Heart Surgery Risk Assessment Tool

Assess Your Surgery Eligibility

This tool evaluates key medical factors that may indicate you're not a good candidate for heart surgery based on current clinical guidelines.

Your Risk Assessment

Heart surgery can save lives. But not everyone who has heart disease is a good candidate for it. Knowing who shouldn’t go under the knife is just as important as knowing who should. Skipping surgery when it’s too risky can mean the difference between recovery and serious complications-or even death.

Severe, Uncontrolled Chronic Conditions

If you have advanced kidney disease, severe liver cirrhosis, or uncontrolled diabetes, your body may not handle the stress of open-heart surgery. The heart doesn’t work in isolation. It depends on your kidneys to filter waste, your liver to process medications, and your blood sugar to stay stable. When these organs are failing, the body can’t recover from major surgery.

For example, someone on dialysis with stage 5 kidney disease has a 30-40% higher risk of dying within 30 days after bypass surgery than someone with healthy kidneys. Surgeons don’t just look at the heart-they look at the whole system. If your other organs are too damaged, surgery won’t fix the problem. It might make it worse.

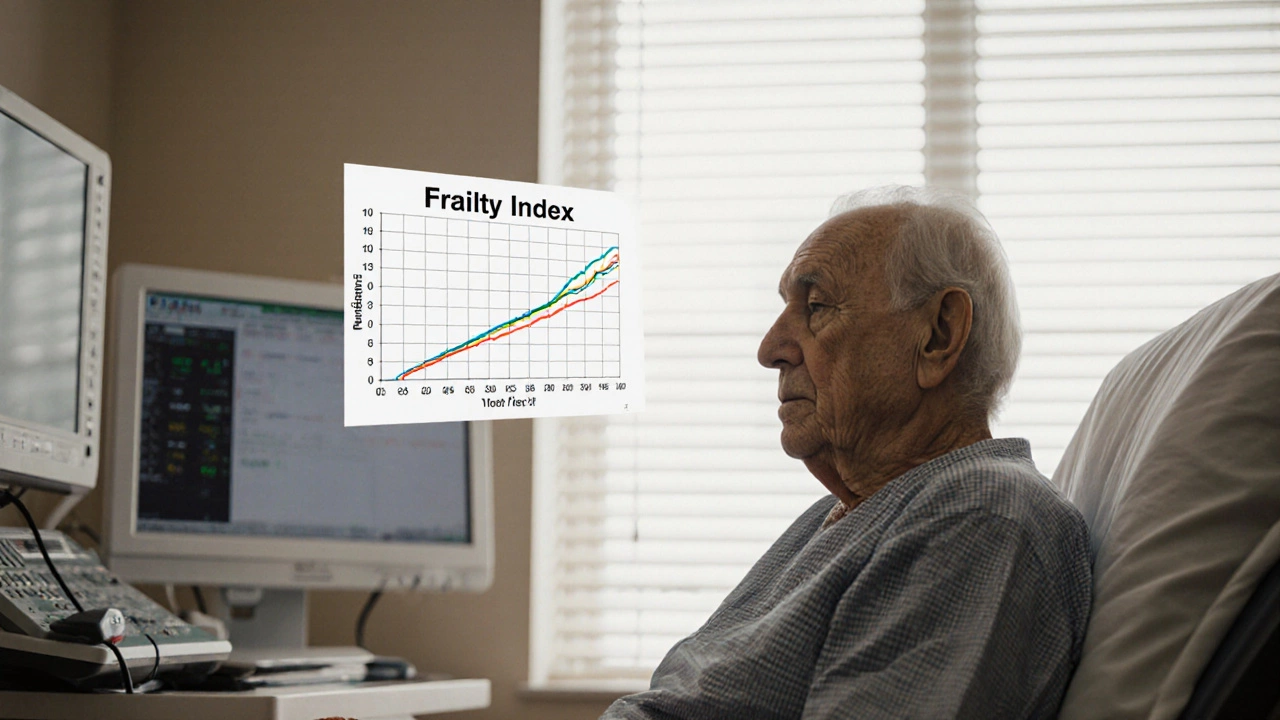

Advanced Age with Multiple Frailty Signs

Age alone doesn’t disqualify someone. But when age comes with weakness, weight loss, slow walking speed, and frequent falls, the risks climb. A 78-year-old who can walk a mile without stopping and lives independently has a very different outlook than a 75-year-old who needs help bathing and gets tired after standing for five minutes.

Doctors use a tool called the frailty index to measure this. It looks at things like muscle loss, memory problems, and how many medicines you take. If you score high on frailty, your body doesn’t have the reserve to heal after surgery. Studies show frail patients are three times more likely to end up in long-term care-or die-after heart surgery than non-frail patients of the same age.

Recent or Active Cancer

If you’ve been diagnosed with cancer in the last year, especially aggressive types like lung, pancreatic, or advanced-stage blood cancers, surgery is usually put on hold. Why? Because heart surgery requires weeks of recovery. During that time, cancer can spread unchecked.

Surgeons won’t risk opening your chest if your body is already fighting a life-threatening illness that needs immediate treatment. Chemotherapy or radiation comes first. Once cancer is in remission-usually after at least six months of stability-then heart surgery might be reconsidered. But even then, survival rates drop if the cancer has already spread to other organs.

Severe Lung Disease

Your lungs and heart work as a team. When one fails, the other struggles. If you have severe COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, or advanced emphysema, your lungs can’t supply enough oxygen-even after surgery. Many patients with these conditions end up needing long-term oxygen after heart surgery, and many never regain their independence.

One study of over 1,200 patients found that those with moderate to severe lung disease had a 50% higher chance of needing a ventilator for more than 48 hours after surgery. That increases the risk of pneumonia, brain damage from low oxygen, and death. If your lung function is below 50% of normal, doctors will often recommend less invasive options first.

Uncontrolled Infections

Heart surgery is a major invasion of your body. If you have an active infection-like a skin abscess, urinary tract infection that won’t clear, or a tooth infection with pus-surgery is delayed. Why? Because bacteria can travel through your blood and settle on your new heart valves or surgical wounds.

Heart valve infections after surgery (called endocarditis) are deadly. They require months of antibiotics and often lead to repeat surgery. Surgeons won’t risk it. You’ll need to treat the infection completely, sometimes for weeks, before they’ll even consider scheduling your operation.

Severe Mental Health Conditions Without Support

Depression, severe anxiety, or untreated psychosis can make recovery impossible. Heart surgery isn’t just a physical challenge-it’s a mental one too. You need to follow strict medication schedules, attend rehab, eat right, and avoid stress. If you’re too depressed to get out of bed, or if you’re experiencing hallucinations, you won’t be able to care for yourself.

Doctors won’t operate unless you have a solid support system: someone to help you take pills, drive you to appointments, and watch for warning signs. If you live alone with no family or friends nearby, and your mental health is unstable, surgery is often postponed-or denied-until you’re stable and supported.

Previous Failed Surgeries and Scar Tissue

If you’ve had open-heart surgery before, your chest is full of scar tissue. That makes a second surgery much more dangerous. Scar tissue sticks to the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels. Cutting through it increases the risk of tearing a major artery or accidentally puncturing the heart.

Each repeat surgery raises the risk of death by 2-3% compared to the first. After two or more surgeries, many surgeons will only proceed if there’s no other option. Sometimes, less invasive procedures like TAVR (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) or stents are better choices than going back in with a scalpel.

Patients Who Refuse Lifestyle Changes

Surgery isn’t a cure. It’s a repair. If you keep smoking, eating junk food, skipping meds, or avoiding exercise, the new valve or bypass graft will fail within a few years. Surgeons know this. And they won’t waste their time-or your life-on a procedure that won’t last.

Many hospitals require patients to attend cardiac rehab and sign a lifestyle agreement before surgery. If you say you won’t quit smoking or won’t take your blood thinners, they’ll say no. It’s not about punishment. It’s about survival. A bypass graft has a 50% chance of failing in 10 years if you don’t change your habits. Surgery is only worth it if you’re willing to protect it.

What Are the Alternatives?

If you’re not a candidate for open-heart surgery, that doesn’t mean you’re out of options. Less invasive treatments have improved a lot in the last decade.

- TAVR replaces a narrowed aortic valve through a catheter in the leg-no open chest needed.

- PCI with stents opens blocked arteries without cutting into the heart.

- Medical management with advanced drugs like SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists can improve heart function and reduce hospitalizations-even in advanced cases.

- Palliative care focuses on comfort, pain relief, and quality of life when cure isn’t possible.

These options aren’t perfect. But for many people, they offer better outcomes than risky surgery.

When to Ask for a Second Opinion

If your doctor says you’re not a candidate, ask why. Get the specific reasons written down. Then, ask for a referral to a heart center that specializes in complex cases. Not all hospitals have the same expertise.

Some centers have teams that include heart failure specialists, geriatricians, and palliative care doctors who work together to find the best path-even for patients others say are too high-risk. A second opinion might reveal new options you didn’t know existed.

Don’t accept a flat ‘no’ without exploring what else is possible. Your life matters. And there’s always a path forward-even if it’s not the one you first imagined.

Can someone with diabetes still have heart surgery?

Yes-but only if the diabetes is well-controlled. Blood sugar levels must stay stable before, during, and after surgery. Uncontrolled diabetes increases infection risk, delays healing, and damages new grafts. Patients with HbA1c above 8% are often asked to lower it first with diet, medication, or insulin.

Is heart surgery possible after a stroke?

It depends on timing and recovery. If the stroke was recent (within 30 days), surgery is too risky due to the chance of another stroke. If it was more than six months ago and you’ve regained most function, surgery may be safe. Doctors will check brain scans and cognitive function before approving the procedure.

What if I’m too weak for surgery but still in pain?

Pain doesn’t always mean surgery is the answer. Medications, cardiac rehab, and palliative care can significantly reduce discomfort and improve quality of life without open surgery. Some patients find relief with nerve blocks, low-dose opioids, or even mindfulness techniques. The goal is to live as well as possible-even if you can’t be cured.

Can obesity disqualify someone from heart surgery?

Severe obesity (BMI over 40) increases surgical risks, but it doesn’t automatically disqualify you. Many hospitals now offer pre-surgery weight loss programs. Losing even 10-15% of body weight can reduce complications. If you’re willing to work with a dietitian and exercise specialist, surgery may still be an option.

Are there age limits for heart surgery?

There’s no fixed age cutoff. Surgeons look at biological age, not calendar age. A healthy 82-year-old with strong lungs, kidneys, and mental clarity can do better than a 65-year-old with multiple chronic conditions. Many patients over 80 have successful surgeries today-especially with minimally invasive techniques.