Surgical Error Prevention Checker

Wrong-Site Surgery

Operating on the wrong body part, patient, or procedure.

Retained Surgical Items

Foreign objects left inside the patient after surgery.

Bleeding Control

Inadequate hemostasis leading to postoperative hemorrhage.

Patient Safety Checklist

Questions to Ask Your Surgeon

- Can you walk me through the "time-out" steps you use?

- Will you show me the imaging that confirms the exact site?

- Who is responsible for double-checking the surgical consent?

- Do you use tagged sponges during this procedure?

- How will you confirm hemostasis before closing?

TL;DR

- Wrong-site/wrong‑patient surgery happens when the surgical team operates on the wrong body part or the wrong person.

- Retained surgical items (sponges, instruments) are left inside the patient and can cause infection or pain.

- Inadequate bleeding control leads to postoperative hemorrhage, which may require re‑operation.

- Standard safety tools - the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist and a mandatory "time‑out" - catch >95% of these errors.

- Ask your surgeon about verification steps and speak up if anything feels off.

Why the question matters

When you’re about to go under the knife, the last thing you want is a preventable slip‑up. Even in top hospitals, surgical mistakes are events that could have been avoided with proper checks and communication. Knowing the three most common errors helps you ask the right questions, spot red flags, and partner with the surgical team for a safer outcome.

1. Wrong‑Site, Wrong‑Patient, or Wrong‑Procedure Surgery

The most eye‑catching error is operating on the wrong area, the wrong patient, or performing the wrong procedure. According to a 2023 safety report, about 1 in 5,000 operations falls into this category - far higher than most people realize.

Wrong‑site surgery occurs when the surgical team mistakenly treats a different body part than intended. The mistake often stems from:

- Inadequate pre‑operative imaging review.

- Poor hand‑off communication between the admitting physician and the operating‑room team.

- Failure to conduct a mandatory "time‑out" before the incision.

Prevention hinges on the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist a 19‑item protocol that forces the team to verify patient identity, surgery site, and procedure. The checklist includes a dedicated "time‑out" where the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and nurses all repeat the key facts out loud.

What to ask your surgeon:

- Can you walk me through the "time‑out" steps you use?

- Will you show me the imaging that confirms the exact site?

- Who is responsible for double‑checking the surgical consent?

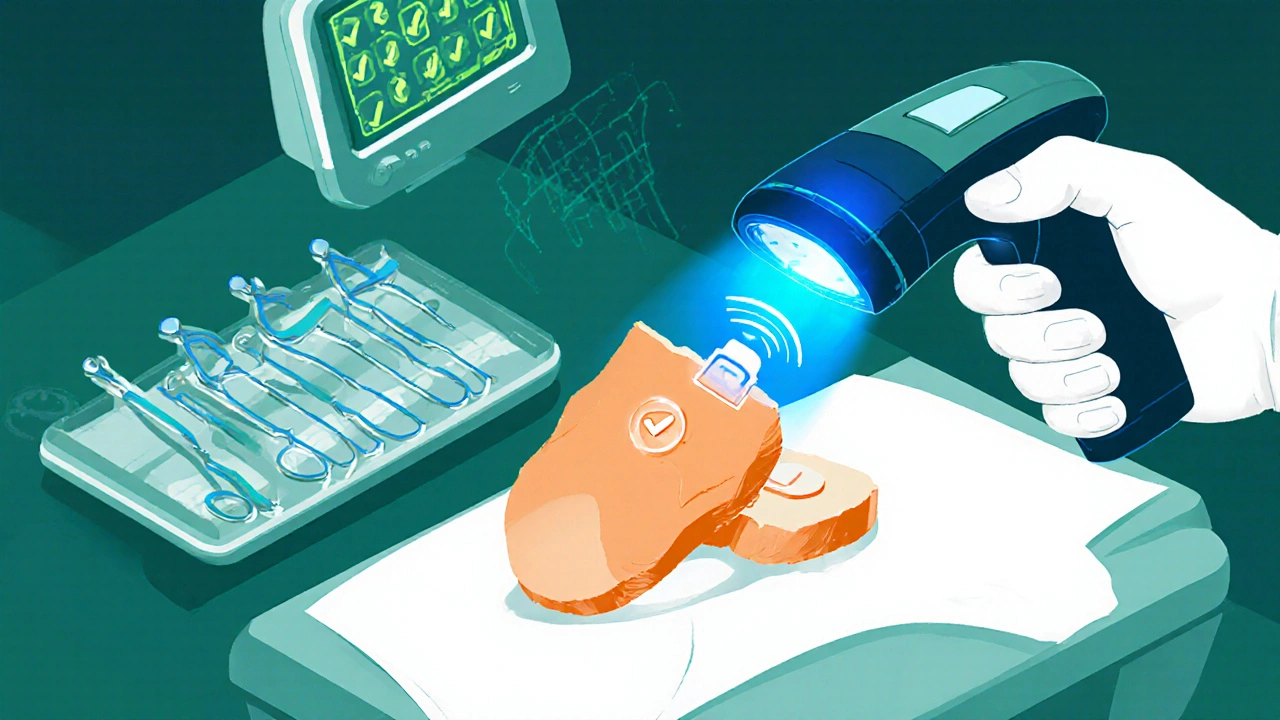

2. Retained Surgical Items (RSI)

Leaving a sponge, gauze, or instrument inside a patient sounds like a horror‑movie plot, but it happens more often than you think. The Joint Commission estimates roughly 1,500 cases in the U.S. each year, with an average cost of $30,000 per incident.

Retained surgical item refers to any foreign object unintentionally left in the body after surgery, such as sponges, clamps, or needles. The root causes include:

- Counting errors: forgetting to tally a sponge before closing.

- Emergency procedures where the usual pause for counts is skipped.

- Complex cases with many assistants and instruments.

Modern ORs mitigate risk with two layers:

- Manual counting backed by radio‑frequency (RF) tags embedded in sponges that trigger an alarm if left inside the patient.

- Digital inventory systems that scan each instrument before and after the case.

Red flag checklist for patients:

- Ask whether the surgical team uses tagged sponges.

- Request confirmation that a final count was "satisfactory" before the incision was closed.

- Know the typical symptoms of a retained item - persistent pain, fever, or unusual swelling.

3. Inadequate Hemostasis and Post‑operative Bleeding

Even when the incision is spot‑on and nothing is left behind, failing to control bleeding can be disastrous. Uncontrolled bleeding supplies enough blood to the wound that clots can't form, leading to a hematoma, infection, or the need for a second operation.

Postoperative bleeding is bleeding that continues or recurs after the surgical wound has been closed. Common triggers include:

- Coagulopathy - a blood‑clotting disorder that may be undiagnosed before surgery.

- Medications such as anticoagulants or anti‑platelet drugs that weren’t stopped in time.

- Technical slip‑ups: missed vessel ligation or inadequate cauterization.

Surgeons guard against this with a systematic approach called hemostasis protocol a step‑by‑step method to identify and seal bleeding sources before closing. The protocol often involves:

- Visual inspection of the operative field for oozing.

- Selective use of cautery, clips, or sutures.

- Application of topical hemostatic agents when needed.

Patients can contribute by:

- Disclosing all blood‑thinners, supplements, and herbal products.

- Following post‑operative instructions - especially activity restrictions that could raise blood pressure.

- Reporting any sudden swelling, bruising, or dizziness immediately.

Quick comparison of the three mistakes

| Error Type | Typical Cause | Incidence (US) | Primary Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrong‑site/Patient/Procedure | Verification breakdown, communication lapse | ~1 per 5,000 ops | WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, mandatory time‑out |

| Retained Surgical Item | Counting errors, emergency pressure | ~1,500 cases/yr US | RF‑tagged sponges, digital count systems |

| Post‑operative Bleeding | Coagulopathy, missed vessel, medication | 2‑4% of major surgeries | Hemostasis protocol, pre‑op medication review |

How to talk to your surgical team

Being proactive doesn’t mean you’re doubting the surgeon’s skill - it shows you care about safety. Here’s a simple script:

"I’ve read about the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. Could you walk me through how your team does the time‑out? Also, do you use tagged sponges, and how will you confirm hemostasis before closing?"

Most surgeons appreciate an informed patient. If the answer is vague or they seem dismissive, consider getting a second opinion.

What to do if a mistake occurs

Even with the best safeguards, errors can slip through. Knowing the next steps reduces anxiety and improves outcomes:

- Stay calm. Panic can cloud judgment.

- Ask for clarification. Request a clear explanation of what happened.

- Document everything. Write down dates, names, and what was said.

- Seek a second medical opinion. An independent surgeon can assess the situation.

- Consider legal counsel. If you suspect negligence, a medical‑lawyer can guide you.

Most hospitals have a patient‑advocate office - use it. They can mediate, arrange additional imaging, or coordinate follow‑up care.

Future trends: technology cutting down errors

Artificial intelligence is starting to flag discrepancies in real‑time. For example, AI‑driven imaging analysis can verify that the planned incision matches the patient’s anatomy, acting as a safety net for wrong‑site surgery. Meanwhile, RFID‑enabled instrument trays automatically log every tool that enters the field, making retained‑item counts almost foolproof.

While tech isn’t a silver bullet, it adds layers that make a single point of failure far less likely. Keep an eye on whether your hospital uses these tools - it’s another conversation starter.

Frequently Asked Questions

How common is wrong‑site surgery?

Studies in the United States report about 1 case per 5,000 operations. The risk varies by specialty, with orthopedics and neurosurgery seeing slightly higher rates due to the precision required.

What are “tagged sponges” and how do they work?

Tagged sponges contain a tiny radio‑frequency chip. After closing the wound, a handheld scanner sweeps the surgical site; if a chip is detected, an audible alarm sounds, prompting the team to locate and remove the sponge.

Can I request a copy of the surgical checklist?

Yes. Hospitals are required by many accreditation bodies to make the checklist available on request. Ask your surgeon or the patient‑advocate office for a copy before the procedure.

What symptoms suggest a retained surgical item?

Persistent localized pain, unexplained fever, swelling, or a palpable lump weeks to months after surgery can all point to a retained object. Imaging such as X‑ray or CT often reveals the foreign material.

How do I minimize the risk of postoperative bleeding?

Disclose every medication, supplement, or herbal product you take. Follow pre‑op instructions about stopping blood thinners. After surgery, avoid heavy lifting and keep follow‑up appointments where the surgeon checks wound healing.